The Collected Letters of Ford Madox Ford in six volumes, phase one of a new Oxford University Press edition, The Complete Works of Ford Madox Ford (General Editors Sara Haslam and Max Saunders) is well underway. The Complete Works will bring the writing of this major twentieth-century literary figure into new focus. Supported by modern editorial and scholarly practices and techniques, volume editors will be able to tell new critical, bibliographical and biographical stories about the range of work, familiar and unfamiliar, published and unpublished, in Ford’s oeuvre. The letters editors have foundational tasks: demonstrating the extent and operation of Ford’s creative and personal networks as revealed by his letters; and foregrounding biographical and bibliographical findings, or any remaining mysteries, contained within the c.3,000 examples of his letters that we now have – the majority of which have not been edited or published before.

This blog article will be the first of several to engage with key questions regarding the letters project: What new light do Ford’s letters shed on the development of his writing life and literary networks? How will they assist researchers on Ford, now and in the future, and scholars of twentieth-century literature more broadly? What role do Ford’s letters play in the making of his literary reputation?

Volume One (1883-1904)

by Sara Haslam

How the letters add to what we know about Ford and his networks

Volume 1 of the letters is notable for its trajectory. The predictably narrow range of correspondents demonstrated early on quickly expands, and in interesting directions, while Ford is still relatively young. The earliest extant letter is to his grandfather, the English landscape and history painter Ford Madox Brown (1821-1893). It is affectionate – and especially apt given Madox Brown’s influence on Ford’s early life and then burgeoning career. A linked, striking exception to the largely domestic letters early on is a well-researched example to the Manchester Guardian (24 May 1892), where Ford wades into a Manchester debate about the value and appropriateness of Madox Brown’s Manchester murals.

Most of the letters we have from 1892-9 are addressed to Elsie Martindale. This is less limiting when it comes to increased understanding than it may sound: these letters reveal the ways in which their relationship and 1894 elopement shaped and spurred Ford’s development as a writer – the fairy tales he was publishing and their teenage angst echo one another in the long series to her. Very soon after this dramatic personal development, his networks include the collectors and contacts related to his work on Madox Brown ahead of the biography Ford would publish in 1896, such as Charles Fairfax Murray, Harry Quilter and, in the US, Samuel Bancroft Jr. Ellen Terry, who had worked with Madox Brown and knew the family, was an earlier correspondent.

(reproduced with kind permission of the Ford Madox Ford Estate)

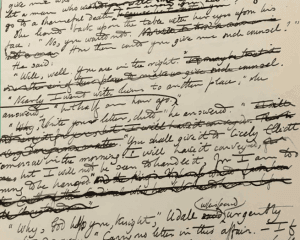

Ford is known for his collaborative fiction projects and publications with Joseph Conrad after 1898, but collaboration is mentioned much earlier in his letters. Ford wrote to Olive Garnett on 13 Feb 1892 (right) after she had, apparently, sent him a story called ‘The Wheel’: ‘That the reading of it has given me great pleasure I need hardly say – moreover politeness demands it […]. I am all anxiety to see how you will finish it but I am afraid that if you asked me to have a hand in it […] the critics would find the juncture at once.’ But Ford and Elsie are described by Ford as ‘working together’, sharing manuscripts by 2 May 1893, and there are many other similar references across this year.

Collaboration was one thing. Ford also admitted to Elsie the difficulty he could sometimes experience when trying to write. The first reference to writer’s block that we have is in a 6 Jan 1894 letter: ‘nothing but hammer, hammer, hammer to produce the smallest mouse of an idea’. The closely woven nature of love and work is made vividly apparent in the letters to Elsie, as is the sense that they were attempting to meet related challenges together.

How the letters will help researchers

Ford’s letters to Elsie have not been collected before. Though biographers, especially Saunders, have quoted long extracts – and even full texts – there is much to learn from close attention to their textual detail, and their frequency. Aspects of postal culture at this time are beautifully demonstrated by the conversational energy these letters display.

(reproduced with kind permission of the Ford Madox Ford Estate)

The letters also have much to offer materially. Ford’s love letters to Elsie were discovered by Elsie’s parents in their hiding place after the couple ran away. They now bear the annotations made – presumably by legal counsel – as part of the court proceedings instigated by Dr William Martindale to try and end their relationship. And many of those same letters, sent by Ford after February 14 1894 until their elopement, are beautiful artefacts (as illustrated, right). They reward focus due to their employment of red ink and monograms – almost certainly inspired by Ford Madox Brown’s visual culture, and more widely that of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

These early letters are not all earnestly or desperately loving. Ford’s humour is also apparent, especially in examples to Olive and Edward Garnett. Many members of the Garnett family were integral to Ford’s early life, personally and professionally. Richard Garnett was keeper of printed books at the British Museum in this period; Olive was a good friend, as suggested above, and her brother Edward, described as ‘the best talent scout of his generation’, successfully took Ford, with Ford Madox Brown’s encouragement, to T. Fisher Unwin in 1891.

Ford’s frames of allusion and reference will also be of interest to the researcher: religious (quotations from both the Old and New Testament – he entered the Catholic church in 1892), cultural (he quotes Shakespeare – principally Hamlet, Browning, Dryden); social – including postal cultures: deliveries and postmen are a constant refrain.

Finally, these early letters reveal how and when Ford’s struggles with his own psychology and mental health began – there is discussion of suicide, and fantasies of their joint death feature in more than one letter to Elsie. Ford writes a letter to Elsie to be opened only after his death. At the same time, love is presented as a talisman against malign and oppressive forces.

The letters to be published in Volume One deepen understanding of Ford’s early life and relationships and, as later volumes will reveal, introduce themes and related practices that would persist throughout his writing life: intrigue, secrecy, the desire to share with a trusted other, to talk, and his need – variously expressed – to look back in the attempt to move forward.