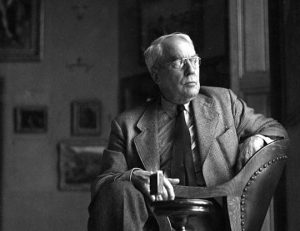

By Paul Skinner

Of her ‘desert island books’, the novelist Penelope Lively wrote: ‘there are three titles that I would pick, because, for me, they are perhaps the ones that have most elegantly demonstrated what the novel can do, where the form is pushed to its limits. And these are: Henry James’s What Maisie Knew, William Golding’s The Inheritors, Ford Madox Ford’s The Good Soldier.’

Fordians will make the mental note that Ford wrote—almost the whole of—a novel called The Inheritors; and hugely admired What Maisie Knew, which was, he once remarked, the first James novel that he read. He also later connected it with the genesis of his great Parade’s End tetralogy: ‘for the rest of the day and for several days more I lost myself in working out an imaginary war-novel on the lines of What Maisie Knew.’

Of her chosen three, Lively found The Inheritors ‘the saddest novel I know.’ Not, that is, The Good Soldier, previously titled ‘The Saddest Story’, which she describes as ‘another marvellous tour de force in which the truth behind a pattern of relationships is revealed with such subtlety and guile that while the reader is never deliberately deceived, each new release of information changes the view of what has happened.’

Most of us will have lapsed, occasionally or often, into the ‘desert island books’ frame of mind. My own case is a tricky one. Greedier than Penelope Lively, I’d have great difficulty choosing three books just by Ford, let alone anyone else, and even then would have to insist on being allowed to count Parade’s End as a single novel—and to refresh the third title on, say, a quarterly basis.

Ford himself was markedly prone to such lists. Probably most familiar is the selection of books that he sent for during his service in wartime France, to see how they would ‘stand up against the facts of a life that was engrossing and perilous’. This was the occasion, which he returned to several times, on which he had the curious experience of ‘so reading’ himself into Stephen Crane’s Red Badge of Courage in Bécourt Wood in 1916 that, when looking out of his tent flap he saw ‘sleepy men bending over fires of twigs, getting tea for that detail, it did not seem real to me. Because they were dressed in khaki. The hallucination of Crane’s book had been so strong on me that I had expected to see them dressed in Federal blue.’

Other strings of titles, threaded through books and articles and essays, include variations on the Bécourt Wood version, bedside lists, men of letters sitting in a study, talking of exchanging books, the ones ‘which, for each of us, are particularly our own.’ Certain authors recur, unsurprisingly, the same titles by the chosen authors too, very often: Flaubert, Turgenev, Conrad, James, W. H. Hudson. There are several appearances by William Beckford, Guy de Maupassant drops in on occasion, as does Stephane Mallarmé, while the Anatole France candidate seems to vary with every telling. On the winnowing side, Ford reflected in one of his pre-war Outlook columns: ‘How much more satisfactory would the history of the English nuvvle have been if we could sweep away the big peaks of the chain—the Thackerays, Fieldings, Scotts—and even Dickens—and if we had only Smollett, Jane Austen, Beckford, Marryat, and Trollope.’ Surprising to some readers is Ford’s admiration for Frederick Marryat, one shared, of course, with Joseph Conrad, of whom Ford remarked that he ‘read with engrossment Marryat and Fenimore Cooper, and so sowed the seeds of his devotion to England.’ (Ernest Hemingway told Allen Tate he had never heard of Marryat, though Tate heard from John Peale Bishop that around 1923 Hemingway ‘kept on his night-table’ a copy of Marryat’s Peter Simple. In 1926, Hemingway wrote to William B. Smith: ‘if you want to read a swell book get Peter Simple by Capt Marryat’.)

But towards the close of Mightier Than the Sword (Portraits From Life in the United States), the actual desert island scenario is evoked, Ford wondering what he should do if he found himself on one—‘midway in the Atlantic’ (a neat encapsulation of what was very frequently his situation in the last decade and a half of his life). He imagines himself ‘reflecting that I should not want immense classics because I should have a hut to build and a garden to dig and beasts to slay and capture. So I should not want the Decline and Fall. . . .’

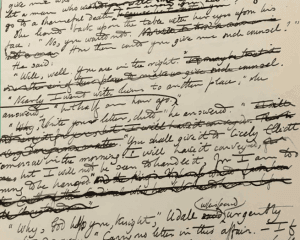

Away, then with those damned thick, square books, what Ford termed ‘the one English prose work that, for its literary quality, can be named beside the great Clarendon’s History of the Revolution, in the tale of huge and unflagging monuments of prose.’ The djinn—who, in this scenario, will collect and deliver the chosen volumes—is showing signs of impatience and Ford, ‘in my haste’, rattles off a dozen volumes, strikingly different in many instances from the usual suspects. There are Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice and Mansfield Park, and Framley Parsonage (Ford’s attitude to Trollope seesawed a little but was finally admiring; also, as he wrote elsewhere, Framley Parsonage ‘must have been the first English novel I ever read’. He also observed that Conrad ‘had a great admiration for “The Barsetshire Novels”’). Mrs Gaskell’s Mary Barton is a newcomer to such lists, as is Emily Dickinson, though Christina Rossetti is not. Ezra Pound’s Cathay both sidesteps the Cantos and looks back to Ford’s review of the volume in 1915 (‘supreme beauty’, ‘if these are original verses, then Mr Pound is the greatest poet of this day’). With Henry James, Ford appears to have made his own idiosyncratic selection for a volume of the New York Edition, containing the ‘Four Visits’ (presumably ‘Meetings’), ‘The Death of the Lion’, ‘The Real Thing” and The Spoils of Poynton. Hudson’s Nature in Downland is a familiar entry, Crane’s collection The Open Boat includes several pieces of which Ford had written with great admiration over the years, particularly the title story, though he referred to ‘The Third Violet’ as his favourite of all Crane’s stories.

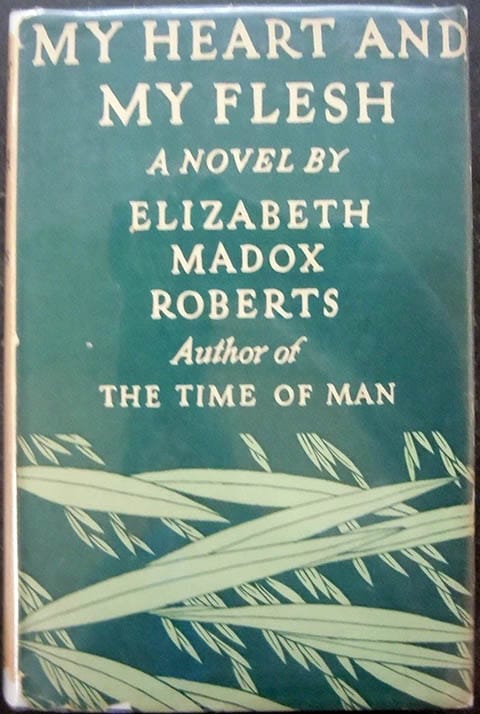

This is not only the latest list of its kind—The March of Literature has a great many recommendations, of course, in its 900 pages but probably enough to sink that desert island—and more varied, finding room for poetry and shorter works. It is also representative of the past decade of his life: with A Farewell to Arms, his admiration for the work of Ernest Hemingway undiminished by Hemingway’s hostility; the first novel by Caroline Gordon, whose gratitude for Ford’s part in its writing never wavered; and My Heart and My Flesh, the second novel by Elizabeth Madox Roberts, perhaps the least familiar of these names now but a Kentucky writer who published her first novel in 1926 and whom Ford unwaveringly supported in the late 1920s and 1930s.

When he died, the desk in his hotel room was piled with manuscripts from aspiring writers—two hundred, by some accounts—still fighting the good fight, still in the lists.