By Andrew Gustar

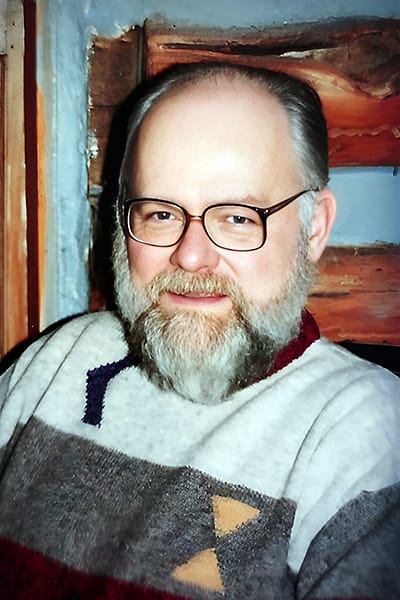

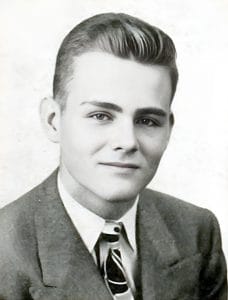

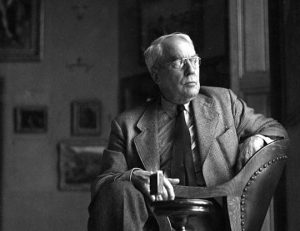

In the first part of this article we followed David Dow Harvey up to the publication of Ford Madox Ford, 1873-1939: Bibliography of Works and Criticism, which remains a hugely important reference work for Ford scholars. David and his wife Mary Ann had settled in Seattle, and in March 1963 they had a son, Christopher. David was teaching at the University of Washington, had just published an article on the neglect of Ford’s novels in England, and was planning a book-length critical study. A promising career lay ahead, but life was about to take him in a very different direction.

In 1964 a new teacher joined Washington’s English department. Five years younger than David, Jocelyn Gilbertson was the eldest of five children from a conservative Catholic family in Eau Claire, Wisconsin, and had just gained her PhD from Cornell (supervised by Arthur Mizener) with a thesis on “Wallace Stevens’ meditative poems”. David and Jocelyn fell in love, and he and Mary Ann divorced. In 1966, David and Jocelyn moved from Seattle to New York state, where he had secured a teaching job at the State University of New York in Albany, while Jocelyn taught at Union College in nearby Schenectady. They married in Fitzwilliam, New Hampshire (to where his parents Lashley and Ernestine had retired) in September 1966.1 Jocelyn’s parents refused to attend the wedding as she was marrying “outside the faith”.

Mary Ann retained custody of Christopher. She went on to earn an MA in Russian Literature from the University of Washington in 1969, and had a successful career in medical research. She died in Seattle in 2013, aged 80. Christopher, known as “Slats”, became a well-known figure in the Seattle punk music scene in the 1980s.2 He died in 2010.

David and Jocelyn became active in the civil rights movement and were conscientious objectors to the Vietnam war. Since the assassination of John F Kennedy in 1963, David had become increasingly disillusioned with his country. In the summer of 1969, in protest at the Vietnam war, the couple took the radical decision to move (with their infant daughter Kerridwen) across the border to Canada, settling on a homestead of 100 acres of hilly, rocky farmland near Barry’s Bay, Ontario.

The farm, which David nicknamed “Gopherwood”, had no electricity or running water. The farmhouse had been empty for five years and was full of junk, and the roof leaked. The well was polluted, but it was soon cleaned and repaired, and provided clear, fresh water.

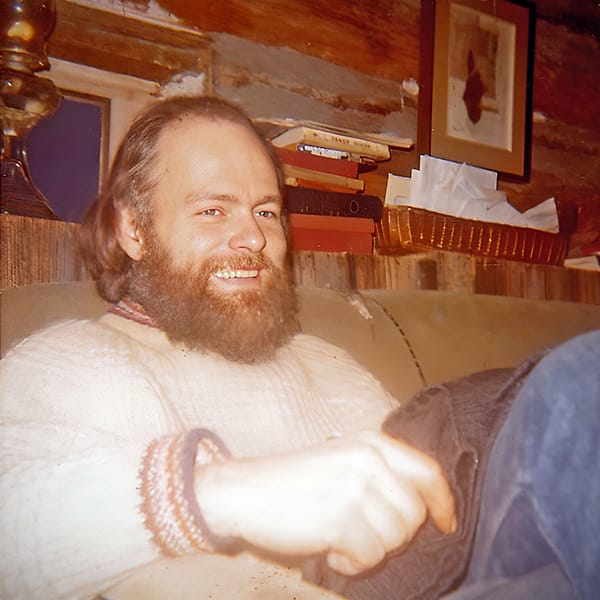

In September 1969, David, with the help of friends and neighbours, started building his own octagonal house, having spent $10 on a design advertised in Popular Mechanics. He published an article about the construction of the house in the Canadian Whole Earth Almanac. The family moved in the following year. There was one large room with dividers separating off two bedrooms, a kitchen, and dining and living areas. David and Jocelyn’s son John was born in the autumn of 1971. Christopher would often visit his father and step-family during the summers, and maintained a good relationship with David into his late teens, when they lost contact.

Life on the farm, especially at first, was tough. David and Jocelyn had read everything they could find about living off the land, and gradually they brought the farm under control and returned it to productivity, growing their own food, keeping chickens and a cow, and even making their own maple syrup, which was boiled down in the family’s bath tub.3

As foreigners, David and Jocelyn found it impossible to get academic jobs in Canada. They planned an anthology of American poetry, but could not find a willing publisher. Their main income during this period was $100 per month from David’s aunt Blanche Hinman Dow, which she contributed as a prepayment of his inheritance. Blanche passed away in 1973, aged 79. Her sister, David’s beloved mother Ernestine, died unexpectedly the following year, aged just 69.4 After “five long winters” on the farm, with little money and two young children to support, the time had come to return to civilisation, and in 1974 the family moved to Ottawa. They continued to own the farm, and spent many weekends and Christmases there.

Despite being granted Canadian citizenship in 1975, employment opportunities for foreign English professors remained elusive. In Ottawa, Jocelyn found secretarial work, eventually working her way up to senior management at the Canada Council for the Arts. David did assorted jobs including taxi driving, but mainly stayed at home, cooking and looking after the house. As Kerridwen Harvey recalls…

“In a time when no one had a stay at home dad, we did. He loved to cook, listen to music (from classical to jazz to rock), read, have good conversations, often fueled by a drink or two, and travel as much as we could with somewhat restrained means. Whenever we had a bit of money, it would mean a trip and some good restaurant meals.”

David also continued to research and write, and took on a few commercial editing jobs. In 1974 he was awarded a grant from the Canada Council Explorations Program: “$4,467 for a study describing the experience of Americans who have emigrated to Canada since the 1830’s”. This project eventually led to a book,5 but the research also generated several journal articles during the 1980s,6 as well as the “Americans” entry in The Canadian Encyclopedia. James Marsh, the encyclopedia’s Editor-in-Chief, later wrote an affectionate foreword to Americans in Canada, saying of David’s move to Canada that “we gained the best that his country could offer”.

In his forties, David developed heart disease and in June 1978 survived a heart attack, followed by another the next year. He had double bypass surgery around the end of 1979. He struggled with the idea of being sick at such a young age, and stopped smoking, improved his diet and started running. David died of a third heart attack at home on 10 April 1990, aged just 58. After his death, Jocelyn sold the farm but remained in Ottawa, where she continued as an activist and champion of the Arts. She died in 2019, aged 82.

A year or so before he died, David updated his CV. He pushed back the date of his Harvard graduation by a year, perhaps to avoid having to acknowledge his military service, which, as a committed pacifist, he rarely mentioned. The list of publications reveals that his book on Americans in Canada had been accepted for publication, and that he had also completed a book “to be submitted for publication” (but now perhaps lost) about the life and letters of his aunt Blanche Hinman Dow. On the final page of the CV, David quotes from some reviews of his Bibliography of Ford, including the following…

- “Surely that prolific and influential, if controversial, author must have stirred pleasantly in his grave at its publication … a careful and thorough job, a model of bibliographic excellence.” (Wilson Library Bulletin)

- “… massive and thorough … Mr. Harvey has done the job as well as it could be done, and it will not have to be done again.” (Times Literary Supplement)

- “In breadth of scope, in thoroughness, and in accuracy, David Harvey has produced a book which must be the starting point for all future Ford scholarship but which also reaches far beyond this limited area.” (Bibliographical Society of America)

- “A huge, granite-solid foundation of bibliographical research, it is scrupulously accurate in detail … and encyclopedic in scope … clearly destined to be the indispensable foundation for future contributions to the Ford revival.” (Critique)

- “It is a matter of some pride to me that my collection formed the basis for David Dow Harvey’s monumental Bibliography of Works and Criticism.” (Edward Naumburg Jr.)

David clearly remained very proud of the Bibliography and its major contribution to Ford scholarship.

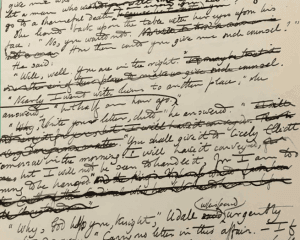

In 1986 David began work on a novel. Eleven pages still exist: an opening chapter entitled “Ulysses at Dawn”. It is clearly autobiographical, set in London, where the central character Bruce Harrison is reflecting on, among other things, life in England, his wife Julie, and the options for their impending return to the United States. Bruce (whom David wanted to be played by Kevin Costner in the film adaptation) has come to London to research his thesis about “Owen Sotheby, your prototypical Englishman … [and] his First World War trilogy, The Last Parade.” His doctorate, like David’s, is with Columbia University, supervised by a prominent Joyce scholar.

The writing style is a little reminiscent of Ford’s, with frequent literary references, non-linear streams of thought, and incomplete ideas left hanging with a “. . .”. Although it was well over twenty years since David had written about Ford, he clearly still had a soft spot for him, and looked back fondly on his time in London.

I think I would have liked David Dow Harvey. He was intelligent, principled, witty, curious, adventurous and a little eccentric. He was certainly proud of his bibliography of Ford, but also of his family, his octagonal house, his pacifism and his transformation of “Gopherwood” farm. David thought he had a story worth telling. I agree.

We will leave the last word to one of David’s friends, who composed the following poem which was read out (in both versions) at his funeral:

vir tantopere nunc tranquilus –

difficile credimus – qui semper

agitans mentis vocis corporis exstitit.

fructum animo ardenti arboris vitae cepit.

sibi structor cum ligno et lingua fuit

nobis instructor convivio.

tu firmitate tantas animi delicias

repperisti quantas fecisti.

vita ut rota revolvit.

ave atque vale.

The man now completely tranquil,

(We hardly believe it.)

who always stood out active in mind, voice and body.

He plucked with ardent animation the fruits of life’s tree.

His own builder with lumber and language, he was

our instructor in conviviality.

You discovered delights as much as

you made merriment.

Life, like the wheel, revolves.

Hail and farewell.

- She is listed as “Mary Jocelyn” on the marriage records, but was always known as Jocelyn or “Josh”. ↩︎

- See https://www.wahmee.com/sk.html and https://jingtuzong.substack.com/p/lets-go-nowherereal-fast-9c7. ↩︎

- Jocelyn wrote about the experience in these articles in Mother Earth News. ↩︎

- Lashley Harvey returned to Eldon, Missouri, after Ernestine’s death, and died there in 1982. ↩︎

- Americans in Canada: Migration and Settlement since the 1840s (Edwin Mellen Press, 1991). ↩︎

- The articles in the Canadian Review of American Studies were “Former American Businessmen in Canada, 1850-1981” (1985), and “The Lure of the North: American Approaches to the Canadian Wilderness” (1986). See also “Garrison Duty: Canada’s Retention of the American Immigrant”, American Review of Canadian Studies, XV (Summer 1985), 169-85: https://doi.org/10.1080/02722018509480811 ↩︎