By Andrew Gustar

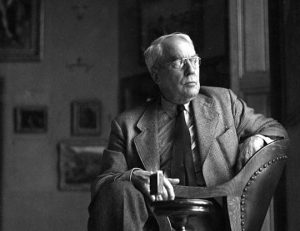

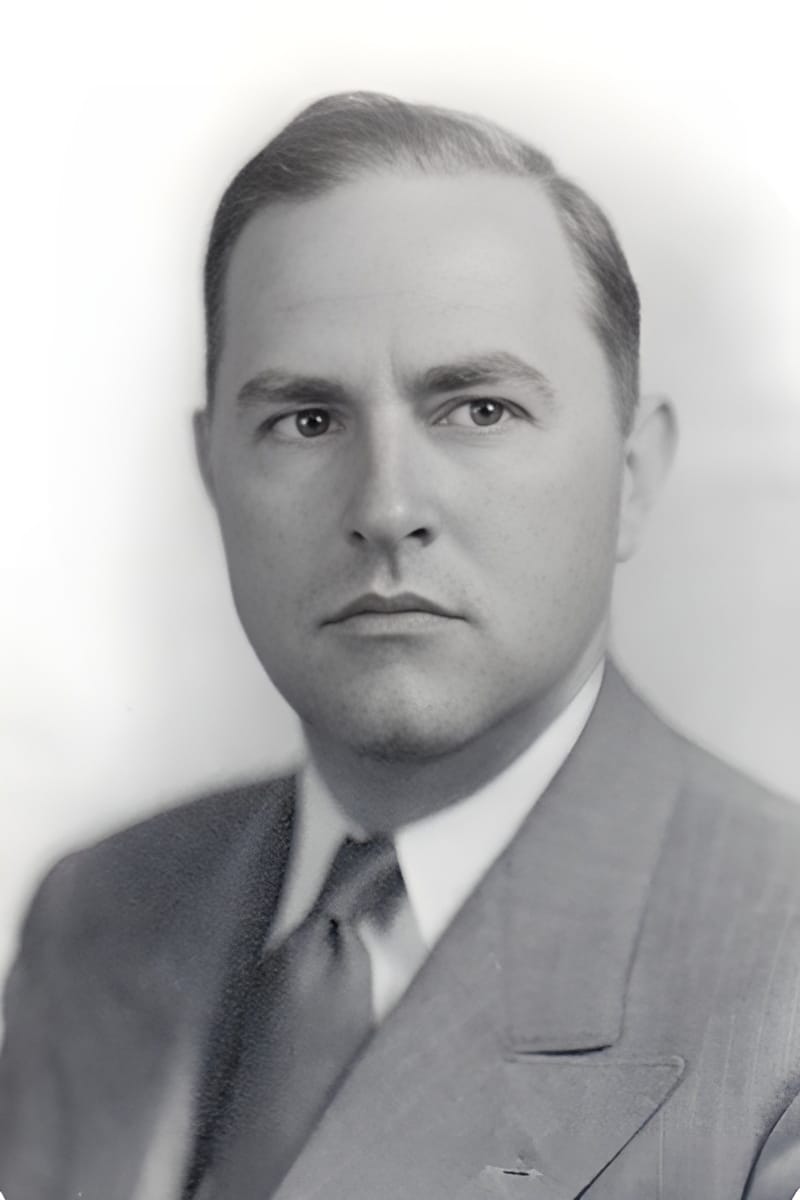

Anybody studying Ford’s works will soon encounter David Dow Harvey’s Ford Madox Ford, 1873-1939: Bibliography of Works and Criticism (Princeton, 1962). In over 600 pages of typewritten text, Harvey sets out details of Ford’s books, articles, letters, manuscripts and other miscellanea, plus articles and books about Ford. Even after six decades, Harvey’s Bibliography remains an impressive and important piece of research. However, despite being the author of one of the most-cited works on Ford, little is known about David Dow Harvey himself. These articles aim to correct that injustice.

David’s story has been pieced together from many sources, including genealogical and census data, newspaper reports, books and articles, school and university publications, and library catalogues. I am enormously grateful to David’s daughter Kerridwen, who has generously provided many details, photographs and documents, and suggested several new lines of enquiry.

David Dow Harvey was born on 30 October 1931 in Alamosa, Colorado, where his father, Lashley Grey Harvey, was Assistant Professor of History and Social Science at the Adams State Teachers College. Lashley had been born in 1900 in the town of California, Missouri, and in 1930 had gained an MA in Political Science from Stanford Graduate School. He married Ernestine Dow (born in Bolivar, Missouri, in 1904) in 1922. David was their only child.

In 1936, Lashley Harvey started graduate study at Harvard, and by 1938 the family were living in Durham, New Hampshire, where Lashley became Professor of Government at the University of New Hampshire. He went on to get a PhD from Harvard in 1942,1 after which he served for three years as a Lieutenant Commander in the US Navy. In 1944 he was posted to Saipan in the Pacific where he was in charge of public education and taught English to the local population, becoming fluent in Japanese. Lashley’s absence during these years perhaps contributed to David finding his father quite a remote figure – he was always much closer to Ernestine.

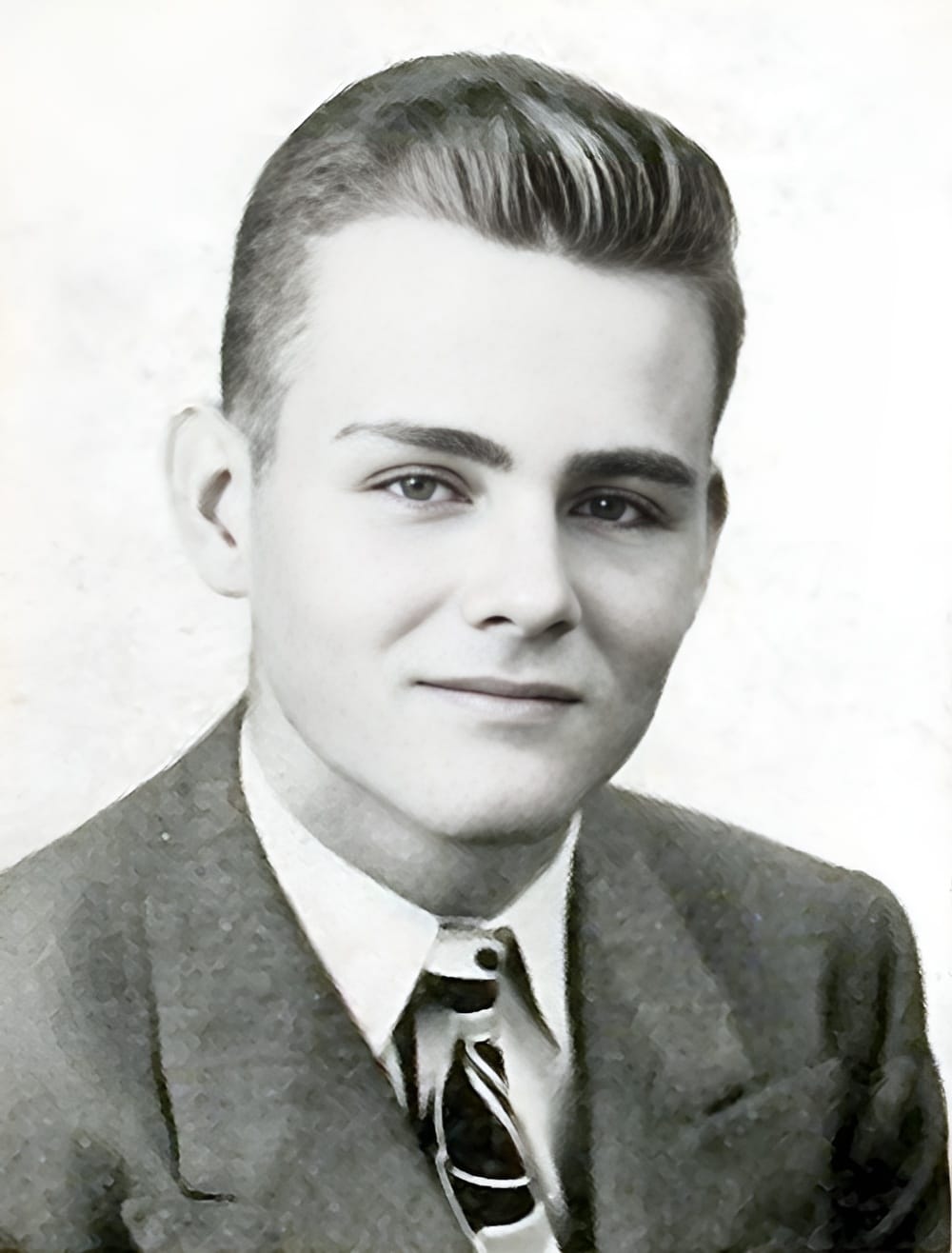

In 1946, the family moved 60 miles south to Newton, Massachusetts, where Lashley became a professor at nearby Boston University and Ernestine worked as a librarian. David spent much of each year at school in New Hampshire, where he attended the residential Phillips Exeter Academy from 1946 until 1950. The 1950 Phillips Exeter Academy yearbook informs us that he was known as “Harve” or “Mose”, and that he was in the Rifle Club, the Jazz Band (he played the trumpet a little), the Glee Club, and the All-Club Football team. At 6’2″, David was also a keen basketball player.

David then studied at Harvard. His second year was a “Junior Year Abroad” at the University of the South West (now Exeter University) in England. His parents accompanied him to the UK on the SS America in September 1951, and within a month he is listed as one of three “transatlantic players” in the university’s first basketball match of the season.2 In June 1952, David returned to the US on the Queen Elizabeth and spent the summer with his aunt Blanche Hinman Dow, Ernestine’s eldest sister, who was president of Cottey College in Nevada, Missouri. He graduated from Harvard in 1954 with a dissertation on “The use of the time-shift in Parade’s End by Ford Madox Ford”.

In 1955, David married Mary Ann Sedgwick, two years his junior, in her home town of Springfield, Missouri. She had just graduated from Radcliffe College (a women’s liberal arts college, subsequently incorporated into Harvard) with a dissertation on “The Theme of Isolation in George Eliot’s Middlemarch”. Shortly before the wedding, David joined the US Army, as did many young men at the time of the Korean War. He hated basic training, but spoke fondly of his posting to Puerto Rico where (like his father) he taught English to the local population.

Leaving the army in February 1957, David and Mary Ann moved to New York, where David completed a Masters degree at Columbia University in 1958 with a thesis on “The Collaboration between Ford Madox Ford and Joseph Conrad”. In Spring 1959, the following announcement appeared in the journal English Fiction in Transition:

Ford Madox Ford: A Call for Aid: Mr. David D. Harvey, who is currently collecting information concerning Fordiana of all kinds, would be pleased to hear of the location of letters or manuscripts other than those mentioned in EFT […] and news of further work in progress in the universities. Please write to Mr. Harvey at 200 West 109th St., New York City 25.

David had clearly already started compiling his bibliography of Ford. Elsewhere in the journal it mentions that he was planning a PhD on “five writers living in Kent [and Sussex]: James, Conrad, Wells, Crane, Ford […] linked by similar use of some techniques which have been called ‘impressionistic’.”

In September 1959, David started teaching at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York. The following May, the Vassar College Miscellany News announced that

David D. Harvey, Instructor in English at Vassar, has been granted a Fulbright scholarship to study English Literature in the United Kingdom next year. Mr. Harvey will be attached to Birkbeck College, University of London, and will do much of his work at the British Museum. Mr. Harvey plans to prepare a critical bibliography of the novelist Ford Madox Ford: and also a study of the personal and literary relationships between Joseph Conrad, Henry James, Stephen Crane, H. G. Wells and Ford.

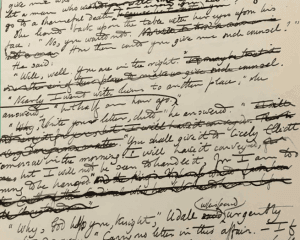

He was clearly changing his mind about the topic of his PhD, which ended up being just the bibliography of Ford. His main supervisor at Columbia was William York Tindall (1903-1981), who was a prominent James Joyce scholar. David and Mary Ann arrived in England on the Queen Elizabeth on 12 September 1960. Based on the people and sources listed in the acknowledgements in the Bibliography, this must have been a busy year, but the couple seem to have enjoyed their time in London. The following year they returned to the US, the thesis (in two typewritten volumes entitled Ford Madox Ford, 1873-1939: a bibliography) was submitted, and David was awarded his PhD in 1962. The thesis, with a longer title and a rewritten introduction,3 was almost immediately published in book form by Princeton University Press. It was dedicated “To My Wife”.

David and Mary Ann did not return to New York, but instead settled in Seattle, where in March 1963, their son Christopher was born. David taught at the University of Washington and continued working on Ford. He published an article “Pro Patria Mori: The Neglect of Ford’s Novels in England” in the Spring 1963 edition of the journal Modern Fiction Studies. The accompanying biographical note says that he “is now writing a book-length critical study of Ford”. A promising academic career lay ahead, but the book-length critical study never appeared and, apart from a couple of book reviews, this article turned out to be David’s last published writing on Ford.

In Part 2 of this article we will discover how David’s life went in an entirely unexpected direction, and will learn about the saga of “Dave Harvey’s Octagonal House”, and an unfinished autobiographical novel…

- Lashley’s PhD thesis was on “Controls relating to state highway administration in Massachusetts”. ↩︎

- One of the other US players in that match – Jim Hollensteiner – now has a sports pitch named after him at the University of Exeter. ↩︎

- Part of the original introduction was subsequently published as a chapter “Ford and the Critics”, in The Presence of Ford Madox Ford, ed. Sondra Stang (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1981) pp.18-24. ↩︎