By Paul Skinner

Glancing at any recent headline, it may come as no surprise that some of us are willingly absorbed in another year entirely, precisely a hundred years back. In publication terms, 1925 might not astonish as did 1922, so often termed the ‘annus mirabilis’ of Anglo-American modernism that the term has come to seem slightly congealed, but it offered, among others, Virginia Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway (and The Common Reader), T. S. Eliot’s Poems 1909-1925, Ernest Hemingway’s In Our Time, Dorothy Richardson’s The Trap, William Carlos Williams’ In the American Grain, Aldous Huxley’s Those Barren Leaves, D. H. Lawrence’s St Mawr and The Princess, John Dos Passos’ Manhattan Transfer, Anita Loos’ Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (with which James Joyce spent three days on the sofa), Marcel Proust’s Albertine Disparue (posthumously) and Franz Kafka’s Der Prozess (ditto), F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy, Mary Butts’ Ashe of Rings and No More Parades, the second in the Parade’s End tetralogy.

It was a hot summer in 1925, and the driest June of the 20th century in England and Wales. The University of Bristol sent a deputation to the 85-year-old Thomas Hardy to award him an honorary doctorate, his fifth. Hardy was one of those admired writers, along with Joseph Conrad, H. G. Wells and T. S. Eliot, whom Ford had approached to give their blessing (and a publishable note) to the launch of his new periodical, the transatlantic review.

In May, the poet Amy Lowell (to whom a Fordian tale or two attaches) died. So too, on 28 August, did the artist William Hyde, who had illustrated Ford’s The Cinque Ports (1900). A friend of Edward Garnett (he had illustrated Garnett’s An Imaged World: Poems in Prose, in 1894), his ‘London Impressions’, accompanying Alice Meynell’s essays in the book of that title, were shown at a private view in December 1898, at which the future Prime Minister, Arthur Balfour, bought two pictures on the spot. In his appreciation of Hyde, in The Artist (January, 1898), Ford remarked of the designs for Milton’s ‘Il Penseroso’ and ‘L’Allegro’ that the ‘individual designs are lovely, and one in particular, a sort of dream-vision of towered cities, is one of the most fascinating conceptions I have ever seen’—which seems to gesture pleasingly (if faintly) towards the epigraph of his 1911 novel Ladies Whose Bright Eyes:

Towered cities please us then

And the busy haunts of men,

Where throngs of knights and barons bold

In weeds of peace high triumphs hold,

With store of ladies whose bright eyes

Rain influence and judge the prize.

L’Allegro

Ford, Stella Bowen and their daughter, Esther Julia, had reached Paris in November 1922. The Transatlantic Review, Ford’s second major editorial project, both began and ended publication in 1924, an astonishingly productive year for him: even aside from the considerable number of contributions in the Transatlantic — serials, editorials, ‘Chroniques’ and the rest — he published his third collaboration with Conrad, The Nature of a Crime, finally in book form; Some Do Not. . ., the first volume of Parade’s End; and Joseph Conrad: A Personal Remembrance, the superb book on his late collaborator, who had died that August.

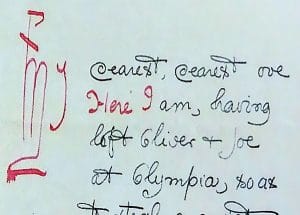

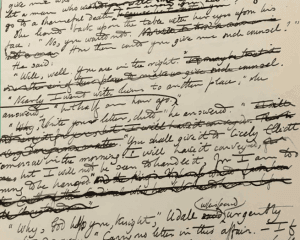

Now, in 1925, dealing with the aftermath of the transatlantic’s demise and romantically involved with Jean Rhys, his contributions to periodicals dwindled almost to nothing. He had been ‘bothered’ by the novel he was working on, he told his agent William Bradley, which hadn’t seemed to come right but now he seemed to have it ‘mastered’ and felt ‘able to look round’. At the end of February, he read some of it to Bradley and, by June, was delivering the page proofs to him; in September, No More Parades was published.

The novel was dedicated ‘To William Bird’, that is, the publisher, journalist and wine connoisseur William Augustus ‘Bill’ Bird, who had shared office space with the transatlantic and whose Three Mountains Press on the Ile de Saint-Louis had published Ezra Pound’s A Draft of XVI Cantos at the beginning of the year and Ford’s own Women & Men two years earlier. In his letter to Bird, Ford wrote that ‘All novels are historical, but all novels do not deal with such events as get on to the pages of history.’ And, also memorably, ‘Few writers can have engaged themselves as combatants in what, please God, will yet prove to be the war that ended war, without the intention of aiding with their writings, if they survived, in bringing about such a state of mind as should end wars as possibilities.’