By Paul Skinner

In the London Review of Books (8 May 2025), Julian Barnes’ notice of Blake Gopnik’s book, The Maverick’s Museum: Albert Barnes and His American Dream (Ecco) includes the observation that ‘you did not need to have met Albert Barnes for him to take against you. In late 1927 Ford Madox Ford, then in New York, telegraphed for permission to visit the foundation. Barnes cabled back: “Would rather burn my collection than let Ford Madox Ford see it.”’

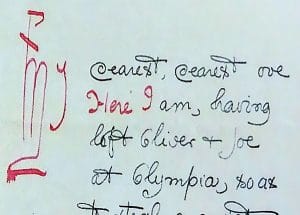

Ford tells that story a decade later in Great Trade Route (he is on a train with Biala): ‘If I put my head out of the window here and craned out a little I should be able to see the roofs sheltering the Barnes Collection of modern pictures. It is said to be the best collection of modern pictures but one in the world. I don’t know.’ He recalls visiting Ezra Pound’s parents in Wyncote, Philadelphia, in November 1927: ‘So I thought it would be nice to see the Barnes Collection.’ The crucial lines follow: ‘I got an intimate friend of Mr. Barnes to get his secretary to cable to him for permission. Dr. Barnes cabled back—from Geneva: “Would rather burn my collection than let Ford Madox Ford see it.”’

Is there more? Of course. There is always more. This is Ford Madox Ford, né Hueffer (aka Fenil Haig, Daniel Chaucer, and one half of Baron Ignatz von Aschendrof), an unstoppable storyteller of whom—unstoppably—stories are told.

Ford had actually asked Jeanne Robert Foster, who had acted in the capacity of American editor of his transatlantic review, to cable Barnes, prompting that extreme response—‘from Geneva’—seemingly bizarre but not entirely inexplicable. Max Saunders (Ford Madox Ford: A Dual Life, II, 324-5) points out that Barnes was not only cantankerous but also a rival collector of John Quinn, the lawyer who had defended in court the editors of The Little Review when they were charged with publishing obscene material (their serialisation of Ulysses) and was, with his huge purchases of manuscripts and artworks (from Conrad, Eliot and Joyce, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Gwen John and Wyndham Lewis), a central figure in that period of Anglo-American modernism.

B. L. Reid, in The Man From New York: John Quinn and His Friends, writes that Quinn ‘heard with anger and envy of the carnage that Dr. Albert Barnes was wreaking among the Paris markets’, writing to Henri-Pierre Roché, his friend, adviser, collector and later novelist (Jules et Jim) in August 1922, ‘If I had the money of that brute Barnes . . . what a time we would have had in the noble art of buying’ (555). The following June, Roché reported to Quinn: ‘Barnes is now ravaging Paris’ (580).

Richard and Janis Londraville (Dear Yeats, Dear Pound, Dear Ford: Jeanne Robert Foster and Her Circle of Friends) note that Barnes had once refused Jeanne Foster’s own request to see the collection—though he relented in 1925 and she visited with Roché—because she was a friend of Quinn, ‘and there had been deep-seated jealousy between the two collectors’ (149).

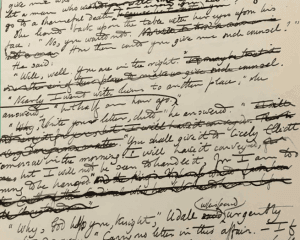

Pencil on buff paper, signed J.B. Yeats / 1917

Any personal animus is probably due then to the Quinn-Foster connection. Ford did write about Quinn though, apart from letters, this was almost exclusively in It Was the Nightingale, not published until the early 1930s. But Quinn had also, of course, put money into Ford’s transatlantic review, a connection which was hardly a secret, certainly in Paris in the early 1920s. And later there was that complicating factor of Jeanne Foster—‘the ravishingly beautiful lady who bought Mr. Quinn’s pictures for him’, as Ford recalled in It Was the Nightingale—promoting Ford’s interests in the United States with publishers and the press, as well as with his lecture engagements.

For a concluding note, there is a letter from Jeanne Foster to Ezra Pound in Rapallo (7 January 1927: Richard and Janis Londraville, ‘A Portrait of Ford Madox Ford: Unpublished Letters from the Ford-Foster Friendship’, English Literature in Transition, 33:2, 1990), responding in part to Pound’s enquiry about Dr Barnes. She mentions that she met him once ‘and had the great pleasure of seeing his collection.’ She appends Barnes’ address before adding this caution: ‘But if he ever fancies that you knew John Quinn, all is over. He has after several years of courtesy to me, apparently discovered that I knew Quinn, therefore I have been refused permission to bring Ford to see his collection. I am now writing to take myself out of it. I dare say Ford will then be admitted.’

Alas, no. There are, noticeably, more than two dozen mentions of ‘Geneva’ in Ford’s Great Trade Route. But that’s another story. Probably.